If this is your first time to visit my blog, welcome! My name is Jordan and I’m a conductor, teacher, and music-lover. This is my blog, the Conductor’s Notebook. To get an overview, visit About the Blog.

This essay is part of an ongoing series on the Art of Rehearsal.

My wife and I love the hit HBO series Hacks; we’ve watched it from the beginning and it’s been wonderful to see the plaudits coming in this season as the audience has continued to grow.

Oversimplified, one-sentence premise: a once rising star comedienne loses everything early on, but continues to work hard, hone her craft, and build her business until she begins to experience a renaissance later in life, with no small number of setbacks and antics along the way as she begrudgingly mentors a young comic writer. Jean Smart and Hannah Einbinder deliver brilliantly as Deborah Vance and Ava Daniels, respectively (and pictured above, L-R.)

Jessica Goldstein does a good job of covering the important beats in her Vulture Recaps of the show - here’s the recap of the most recent pair of episodes (Season 3, Episodes 7 & 8, which were released together last week).

But in watching this past episode, I was fascinated by the scenes where Deborah joined an improv comedy troupe for a performance, and it seemed like maybe there were some lessons for us all about how to work on a team and how to both lead and follow. In short, it seemed like there were some lessons about rehearsal worth exploring.

The Magic of Improv

Cards on the table: I believe that one of the most useful ways to think of rehearsal leadership is as a form of improvisation. Starting last summer I began to think of the way in which the score, the ensemble, the space, and the time constraints of a rehearsal all provide a framework for something akin to jazz. There are chords, instruments, melodies, and rhythms that might be appropriate, and the soloist is free to try many things, but there are differences between deeply seasoned improvisors and young students, for instance.

Put another way, our nephew CJ is a fantastic tenor sax players. But there are differences between C.J. and Coltrane, you could say. (Though in all candor, there is no difference between the two in terms of my enjoyment level!)

Point being, you have degrees of freedom, but jazz is built around some structure, some freedom, and the expertise necessary to artfully surf those structures in realtime.

Back to Hacks

What does this have to do with Hacks? Let me unite these two strands around the idea of improvisation:

Last week, we saw Smart’s character, Deborah Vance, put into a novel scenario: as part of a PR blitz related to a larger story arc, she goes to a university to receive an honorary degree, and included in her visit is an invitation to participate in the university improv troupe’s evening performance. Goldstein for Vulture:

Ava tells her correctly that “improv has never made anyone look good.” The whole improv scene is terrible, by which I mean perfect, from the dopey alliterative introductions to the use of “Who Let the Dogs Out.”

In short, it’s terrible because Deborah has never done improv and doesn’t understand how it works. I’m telling you, it’s a great scene.

How Improv WorkS

According to Second City, the fundamentals include: “impulse & spontaneity, listening, being present in the moment, taking risks, finding agreement (making & accepting offers) and other basic building blocks of improvisation.”

According to Preston Smith (no relation), the core aspects of comedy improv include:

1. Listen – As simple as this seems, it is probably one of the most difficult skills to master. Listening will free you from having to think of what you are going to say a head of time.

2. Agreement (Yes, And…) – Assuming you have listened, you will be able to agree with what was said AND add information. Agreement is what allows a scene to progress!

3. Team Work (Group Mind) – Improv is a vast mechanism of give and take and support. The group mind is greater then the individual.

Deborah wasn’t able to produce any of these qualities. The scripted comedy came from the juxtaposition between her attempt to control scenes that were meant to be spontaneous. Yet, spontaneity came with structure.

For me, this episode also contained an element of kismet. This weekend I read Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink. There is a section of the fourth chapter titled “The Structure of Spontaneity,” which opens on an improv comedy group performing a Harold - in which they take a topic suggestion from the audience and, "without so much as a moment's consultation, make up a thirty minute play from scratch."1

This was the same type of scene which Vance ruined (and Smart nailed). Why was Deborah so bad? For this, let’s return to the scene just before the dumpster fire and look for clues…

Talent or Preparation?

We already glimpsed Deborah’s many failures in their warm-up, where she had no idea what to do.

Clue 1: Deborah was not familiar with the warm-ups – drills which help the troupe warm-up their minds and bodies. Step 1 would be to regularly practice these warm-ups so that the pre-performance warm-up is a mere reminder, a pointer to all of the work she had done in the past. Here is a famous stand-up comedian asked to work in a different comedy discipline where her many years of skill were of no use. In the warm-up, we see that the students, on the other hand, were extremely well-prepared. This wasn’t wasn’t a case of lack of talent, in other words, this was a lack of preparation.

Gladwell summarizes it thusly:

The truth is that improv isn’t random and chaotic at all. If you were to sit down with the cast… you’d quickly find out that they aren’t all the sort of zany, impulsive, free-spirited comedians that you might imagine them to be… Every week they get together for a lengthy rehearsal. After each show they gather backstage and critique each other’s performance soberly.

Far from a talent driven act of play, actors treat improvisation as serious work full of rehearsal, discipline, and critical reflection. Back to Gladwell:

Why do they practice so much? Because improv is an art form governed by a series of rules, and they want to make sure that when they’re up onstage, everyone abides by those rules.

This brings us to Clue 2: Deborah doesn’t know the guiding philosophy. Preston Smith explains the importance of acceptance - of “yes-and”-ing your colleagues to keep the flow going. Deborah immediately negated this flow, which forces the troupe leader to explain it to her.

In Blink, Gladwell’s troupe goes on to compare improv to yet another domain, basketball. Basketball was a favorite sport of mine in elementary school, though I was not great at it - and the reason I wasn’t great probably has something to do with the problems that Deborah Vance faced. Gladwell explains:

Basketball is an intricate, high-speed game filled with split-second, spontaneous decisions. But that spontaneity is possible only when everyonee first engages in hours of highly receptive and structured practice – perfecting their shooting, dribbling, and passing and running plays over and over again — and agrees to play a carefully defined role on the court.

In short, he says:

Spontaneity isn’t random… How good people’s decisions are under the fast-moving, high-stress conditions of rapid cognition is a function of training and rules and rehearsal.

Deborah, skilled as she was as a comedian, had no chance of success given that she worked in a different medium (stand-up), and had no experience with improv, making this failure howl-worthy.

Lessons for Musicians

This brings me back to jazz and finally back to rehearsal.

I believe that the skills conductors need in rehearsal are neither ephemeral nor insubstantial; to the contrary, they are thick and laden with challenge. But they are frequently difficult to discern without experience.

Some of that is unavoidable. But I think that some of it is also due to the lack of available literature on the topic. Because young conductors often have few opportunities to conduct, it behooves the profession to do what we can to make visible those aspects of rehearsal which can be described and explained. These include some issues such as sonority, phrasing, articulation, balance, and precision which do come up from time to time in classes and workshops.

In addition, there are a wide variety of procedural questions about:

what to say,

how to say it,

when to stop and fix something, and

what to do next,

…as just a few examples of the tactics which receive very little discussion.

And if described fully, they would reveal the improvisatory character of rehearsal in a way which score study alone would not. As critical as conducting technique and score preparation both are, there is more to it than that.

However, Deborah, for all her lack of skill in improv comedy, shows tremendous procedural knowledge at the top of the episode during a photo shoot, just one of many examples of the lessons that she teaches her young apprentice. When Ava compliments her tremendous skill, she responds almost by rote with a crisp and clear procedure for striking the perfect pose:

Ava: Fierce! You’ve gotta teach me how to take a photo like that!Deborah: Chin down, nose forward, eyes up, and hum the national anthem, keeps the jowls tight.Life is full of little procedures which are not rigid, but provide a structure for interesting variation. Rehearsal is a perfect place to take stock of the many procedures we use to get the work done and collate, consolidate that knowledge, to spread better and better practices across the music world.

Many terrific teachers and thinkers are working out the shape of these things.

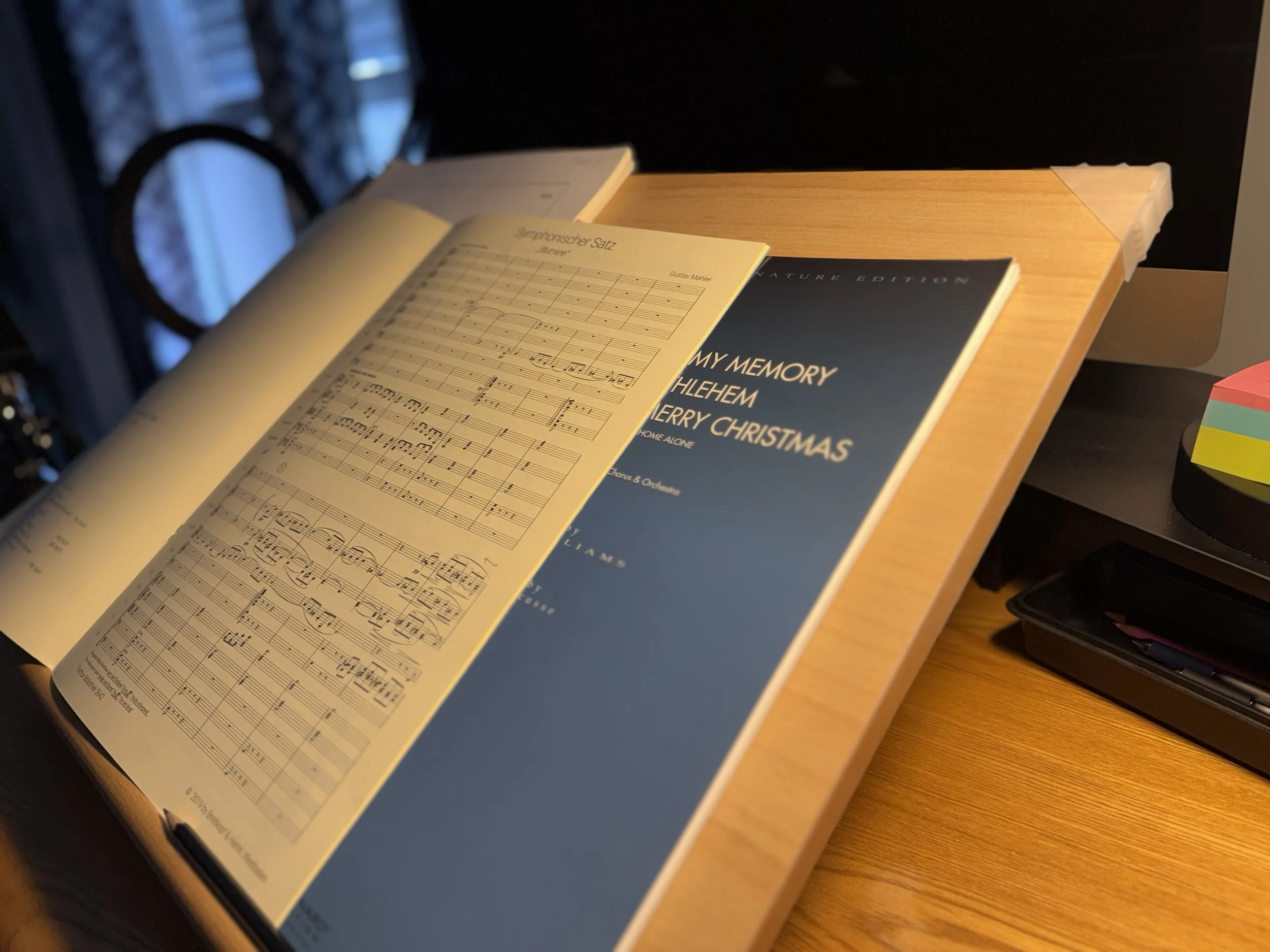

Claudio Abbado in rehearsal with his Mahler Chamber Orchestra. Click through to read a wonderful story about Abbado's ability to get and keep the sonority he was looking for, as told by the musician who posted this video, in the video description.

Chamber music research seems to be one of the most interesting places to look for interesting writing, due in part to the limit on the number of people and interactions to try to monitor. It's also a great place to go because, as Gary Lewis frequently points out, orchestral music is at its best when it is approached like large-scale chamber music. The Claudio Abbado-founded Mahler Chamber Orchestra might seem like a contradiction, if not for this strong connection. And lastly, it is fascinating for our purposes, for all of the same reasons that improv comedy is fascinating - it is another pure enactment of the three core principles we learned from Preston Smith: Listening, Acceptance, and Group Mind.

And rehearsal is where the groundwork is laid for that magic, as Roesler and others continue to document.

I hope that the next 10 years will be a time in which many such resources will be created. I am working on some of those myself. In the meantime, what can we do?

To answer that we might ask, given what we’ve learned, what Deborah Vance and Malcolm Gladwell might advise. I think it would probably be that young conductors should take some time during score prep to rehearse their rehearsals.

Rehearse your Rehearsal

Far from fiction or a tangiential metaphor, that is exactly what I’m proposing. But don’t take it from me.

Marin Alsop often says that when she was just starting out, she would sit with her score, make a rehearsal plan, then sit and time herself with a stopwatch as she practiced verbalizing a suggestion for an anticipated rehearsal challenge, working out both the wording, and developing a sense for how long it took to fix things as she tried to assemble her rehearsal plan. That’s right: she rehearsed her rehearsals!

Gladwell goes on in the book to describe one of the important benefits of Alsop’s suggestion: by preparing those elements of rehearsal that we can, it frees our limited cognitive resources to attend to many other issues that emerge during rehearsal.

Marin would be the first to tell you that, as she would say, “if things don’t work according to plan, you need to get a new plan, fast.” That is (borrowing from our three metaphors), just as you move through the “chord changes” of a jazz chart, or execute the various “plays,” or utilize various routines like “the Harold,” so to do conductors have certain tactical procedures which they can use almost without thinking in order to achieve certain outcomes.

Donovan Mitchell (45), E’Twaun Moore, Thursday, Jan. 16, 2020. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

One classic example would be the root-fifth-third method of tuning a chord. This sequence is well-known and well-subscribed by many excellent conductors as a tried and true method for quickly getting a chord in tune by following the laws of acoustics. There are many procedures like these that we can quickly turn to when the need arises, yet very little of this has been systematically explored. It seems to me that in order to advance our craft, we need to get a better handle on what is going on in rehearsal, both for ourselves and in order to ease the path for our students.

When I would get picked up from Basketball practice as a kid, my Dad would cheekily ask “how was basketball rehearsal tonight?” Though in hindsight, perhaps he wasn’t as cheeky as I suspected at the time. After all, and perhaps not totally coincidentally, one of the NBA’s teams is the Utah Jazz.

Coda

The title of Hacks, up until now, has to my knowledge, never appeared in the text of the show. But like the Grapes of Wrath, it finally showed up at a late-breaking, dramatic moment, the final catalyst to kick off the biggest moment of the show so far. Ava, in an uncharacteristically sober tone, reading from a recent article on Vance, intones:

““A Hack is someone who does the same thing over and over. Deborah is the opposite. She keeps evolving and getting better.””

In an episode full of implications for rehearsal technique, this was almost a straight-to-camera exposition of the point of the show (something much broader than my narrow purpose here), and also a description of the rehearsal process, as well as our longtime goal as practitioners of our art, all rolled into one: to evolve and to keep getting better.

1. Malcolm Gladwell, Blink (New York: Black Bay, 2005), 111-115

2. Rebecca Ann Roesler, “Development and Application of a Framework for Observing Problem Solving by Teachers and Students in Music,” (PhD diss.: University of Texas, 2013), https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/21569.

3. Rebecca A. Roesler, “Toward Solving the Problem of Problem Solving: An Analysis Framework,” Journal of Music Teacher Education 26, no. 1 (October 1, 2016): 28–42, https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083715602124.

4. Rebecca A Roesler, “Fantastic Four! Problem-Solving Processes of a Professional String Quartet,” Psychology of Music 50, no. 2 (March 1, 2022): 403–21, https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735621998746.

Cover Image Courtesy HBO