Image Credit: NASA / ESA / CSA

In Texas last month, I worked with an outstanding (and enormous) orchestra made up of high school students working on music by Prokofiev, Marquez and Tchaikovsky. Their horn section was (I’m rounding down here) approximately seven miles from the podium. Yet, astonishingly, they managed to stay on top of the beat! This is a rarity for a horn section, but why is that?

Meanwhile the flute section, a mere 6 miles away, struggled to stay linked up with the strings in certain passages. What makes a section play together, or struggle to do so? Is it preparation? Is it watching?

The key to successfully navigating ensemble precision issues often boils down to an awareness of the challenges presented by certain spatial situations: distance and direction in space create incongruities in time.

Into this field step the marching band and drum corps experts who will no doubt understand these ideas better than most other musicians. They are dealing with an order of magnitude more space, in which the difficulties of sound delay are increased and they become a constant and essential rehearsal priority. If the thing comes unglued, it’s a calamity.

Because the rest of us deal with the problem in smaller doses, it is easier to overlook, but we do so at our own peril. Time and time again I see rehearsals with even professional musicians where ensemble issues have certain general, predictable tendencies which if handled correctly, can be solved quickly. Unfortunately, I sometimes see where an otherwise fantastic conductor wastes valuable rehearsal time trying things again and again without making a simple coordination fix that follows these acoustical principles.

Here are a few guidelines to increase ensemble precision and apply the wisdom of the marching field to the opera stage and the concert hall.

1. Sound must always travel back to front.

Never forget: sound is slow!

(Don’t take my word for it! See here and here.)

First, some fundamentals. Our minds tend to merge sound and sight together into a single, “unitary percept,” meaning that sound and light don’t reach us at the same time, but our brains adapt to make it seem as if they do. In a large or even medium-size orchestra, the slowness of sound is already playing a disruptive role whether we can see-hear it or not.

Bottom line: If you are an orchestral brass player enjoying the sounds in front of you, you are already poised to enter late.

(NB: I’ll keep referring to brass from here on out, thinking of an orchestral brass section, but this same problem can apply to basses, percussion, harps, backs of violin sections, and certainly applies to choirs set up behind a band or orchestra, and to opera and musical theater. I’ll simply use orchestral brass as the stand-in for these many cases.)

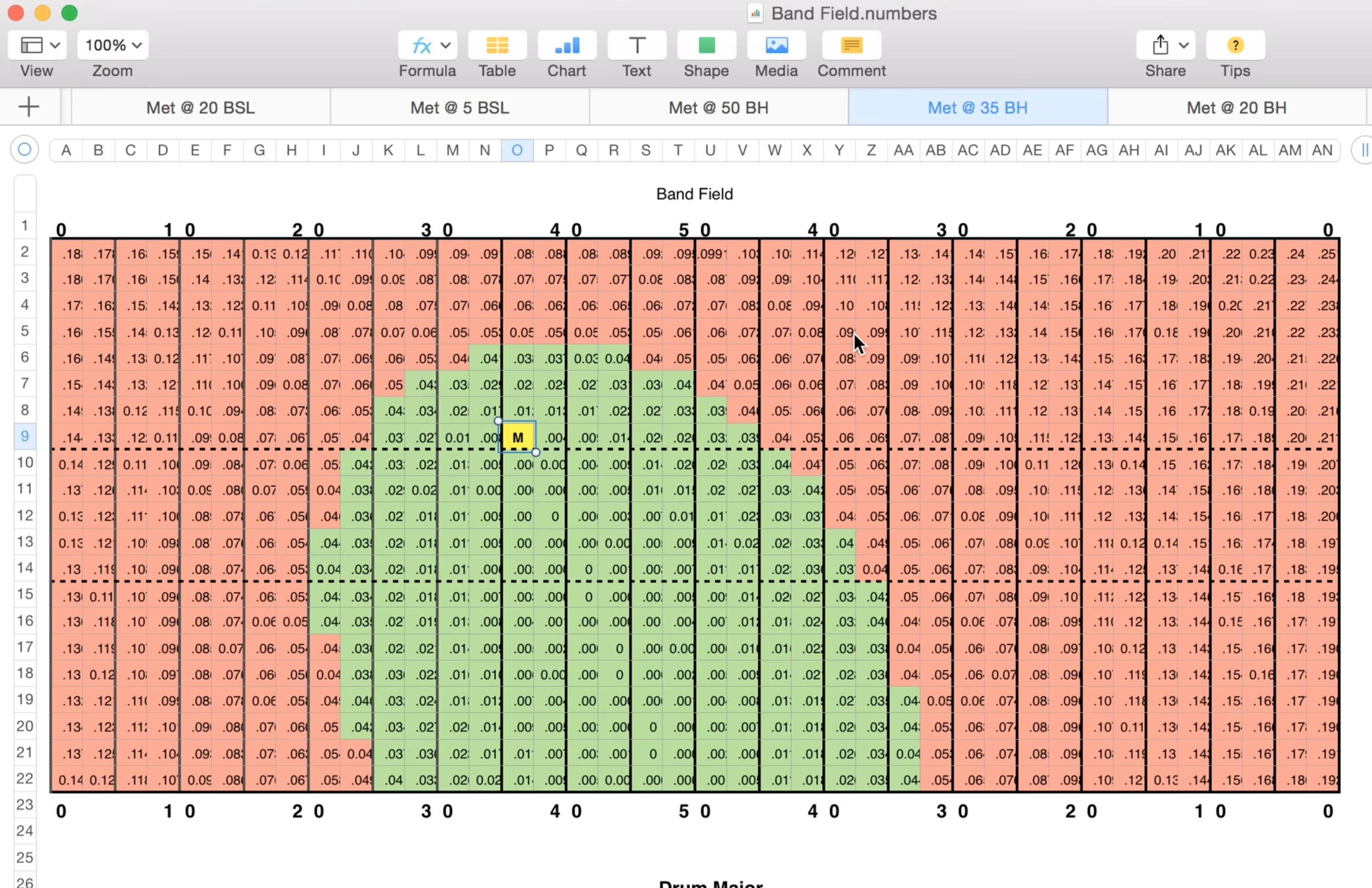

Above, I provided some of the biology. How about the physics? Andrew Rogers has done an outstanding write-up of the math, going so far as to work out the precise delay across space, and organizing the amount of space in which a unified sound is generally possible. See here for the video and here for the excel spreadsheet.

Screen Grab from RRR Woodworks. This is a picture of sound delay. Note that all of the area in front of the temporal center of the group is a safe place to coordinate, but often, those musicians should be listening back and not watching.

What?

Let’s move this back to the concert hall. As the sound travels away from the strings in all directions, it is already in the process of traveling to the audience, even as it is also traveling backwards to the ears of the brass section. A brass section playing strictly with what they hearwill then begin to play, but by the time their sound reaches the audience, the string sound has already landed. Picture running a race in which you first run 10M in the wrong direction, and then begin running in the right direction: you’re not just 10M behind, you’re now 20M behind the person who took off in the correct direction! (Horns are even worse - their bell is pointed in the wrong direction!) For an excellent demonstration, see from 1:30 to 5:30 of Bill Bachman’s demonstration on YouTube.

How?

To fix back-to-front problems and direct the flow of sound forward, consider the following steps:

Ask brass to play with the stick and ignore what they hear in front of them.

Ask brass to play “sooner than you think you ought to.”

If you have a brass or woodwinds entrance to conduct, gently scoot forward in time to give the entrance.

Yes, I’m telling you to deliberately rush to prepare the entrance ahead of the sound you’re currently hearing. Then, immediately drift back “in the pocket” on the following beat or two.

Best case, you never talk about this, you only show it. However, if this provokes the strings or woodwinds into rushing, let them know to play with what they hear behind them there, and not to worry about you. If you absolutely must, you can let them know that you’re making sure to meet up with the brass.

Doing this is simply never a problem. I do it all the time.

Talking about it with musicians who don’t know about this maneuver can sometimes be a little disconcerting and cognitively difficult to digest. It’s possible to make things worse with our words even if the technique is sound! (Younger musicians are of course more open to this.)

2. Side to Side? Listen in.

Likewise, certain lateral challenges crop up. Oftentimes, basses and cellos might need to coordinate their pizzicatos with a far-away-harpist or pianist, or a bass clarinet needs to play with marimba. Or a timpanist and a bass drum player might need to align across the room. A conductor might be tempted to ask everyone to watch him closely, and that’s generally good advice for people towards the back.

In most cases, it is best to listen in to the center, even if those players are playing a different type of part.

Put in the reverse, it’s often worse to try to coordinate with extreme stage right and left, even if they share the same part or similar rhythm.

If it’s necessary to ask the sides to coordinate directly, it’s best to ask one side to watch the conductor and for the other side to watch the first side. This is sometimes easy to do, but sometimes challenging if the player struggles to see the particular players.

That may be a time to slightly adjust the setup if it creates a possibility to see one another play (bow on string, mallet on drum head, fingers on harp strings, etc.). If applicable, try to ask the players to recall this detail before the next rehearsal and double check that the setup reflects the needed line of site, that is, check their line of sight.

3. Lower = Slower

Additionally, tessitura plays a compounding role in addition to space issues. Because lower voices are often somewhat grouped together, you have contrabassoon, tuba, and bass toward the back of the space stage left, with violins closer to the audience and stage right. Given that lower instruments each respond more slowly in their own way, this creates additional opportunities for delay. Add in the possibility that percussion, though they are technically in the back row and further from the conductor, are sometimes spread out almost to the lip of the stage, closer to the audience.

When a tear is noticeable, ask low instruments to begin to breathe sooner. Oftentimes, it is the lateness of the breath causing the late entrance.

In delicate passages, sometimes with problems of tessitura, players might be tempted to play late in order to not stick out. This might be great in some circumstances, but if the coordination problem is greater than the balance problem, then reassure the players not to worry about balance for just a moment and play on time with a great sound at a comfortable mp. After finding an in-time entrance, you can then work backwards to performing the same precise entrance at a softer dynamic.

4. Pointy sounds need to play in the head of the comet.

Some instruments and techniques are smooth and breathy and many sounds can seem to come together even if the entrance is not precise. Combine these ideas with nos. 1 and 3 above, and you end up with scenarios where a xylophone player playing with the first violins will cut through and have a head start over the slower instruments who also start their slower instruments from positions further back.

Violin pizzicatos, snare drums, triangles, xylophones, and harps are some of the worst offenders. They may be tempted to place their notes directly with the conductor’s stick. For percussionists, this is especially tempting. Consider the isomorphism between the conductor’s baton and their mallets, sticks, and beaters: Baton down=stick down, they might say. Right?

Wrong.

These instruments cannot help but announce themselves and produce their sound far more immediately than cellos playing arco legato. As a result, they need to learn to compensate globally (in all or most musical situations). That is, virtually every note they play (within certain types) will need to be later than the baton, and later than believe the musicians around them might begin to play. I call this the “head of the comet” - it’s at the center of the mass of sound, but not on the flaming front edge.

The corollary is that French horns almost always need to play sooner than they think they ought to.

5. Anchor to existing skill sets.

In the finale to Shostakovich 10, the trumpets are asked to join the Horns in the traditional role as the upbeat kings.

Otherwise fantastic trumpet players sometimes struggle in this role and lose time. It’s important to notice that these players are working together so that if a tear occurs, you can ask the trumpets to lean on the horns. This is also a situation that brings up seating arrangements. It might be advantageous to avoid a single brass arc that divides trumpets and horns in a case like this. Instead, one might place the horns in some kind of block arrangement not too far from the trumpets, limiting the degree of right-to-left challenges.

I’d love to hear how you’re navigating these spatially complex musical scenarios. Please get in touch to share your stories.