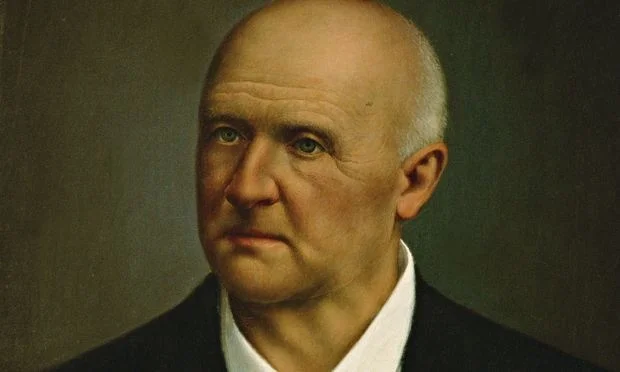

Anton Bruckner is perhaps most immediately identified with the bombastic, brooding, and brassy sound of his massive symphonies. But, imagine stripping all that away. What are you left with? It turns out, there is a rich vocabulary that is striking for its clarity and purity at nearly every turn.

Some of the musicians I most admire have looked rather askance at the notion of sanding down a Brucknerian symphonic landscape to just 11 musicians, as was done by Schoenberg and his entourage, and as will be done as my colleagues at Symphony Number One and I perform it this weekend. And they look askance for good reason: It seems to go against the fundamentals of what Bruckner’s music is all about! But, if you take off the brass clothing, there is much left of the interior life of his music to be discovered.

“reverence for The Divine, for The Higher Ideals, and for Our Better Nature. In a word, God.”

I think one of the reasons I find this so appealing is that I didn’t initially discover Bruckner through his symphonies. My initial vector was through singing his motets in college. So, I think I never formed my mental Bruckner totem around his orchestrations but rather around his harmonic language, expressed in a capella choral music, as a tool to focus on reverence for The Divine, for The Higher Ideals, and for Our Better Nature. In a word, God.

The result, to my great fortune, is that I find a presentation of a Bruckner symphony with chamber orchestral forces to be as exhilarating and perhaps even more challenging than to perform it with a large orchestra.

Going into a detailed discussion on the mechanics of the music is beyond the scope of this particular space. But let me just say that there is something to be said for the idea. It is not a “reduction” in the literal sense. On the contrary, it is a distillation, concentrating the things that matter most into the smallest possible form.

Related Video

Bruckner's Symphony No. 7, Mvt. I. Allegro moderato. Performed in an intimate arrangement for chamber orchestra. Performed by Symphony Number One at the Baltimore War Memorial on October 21, 2017.